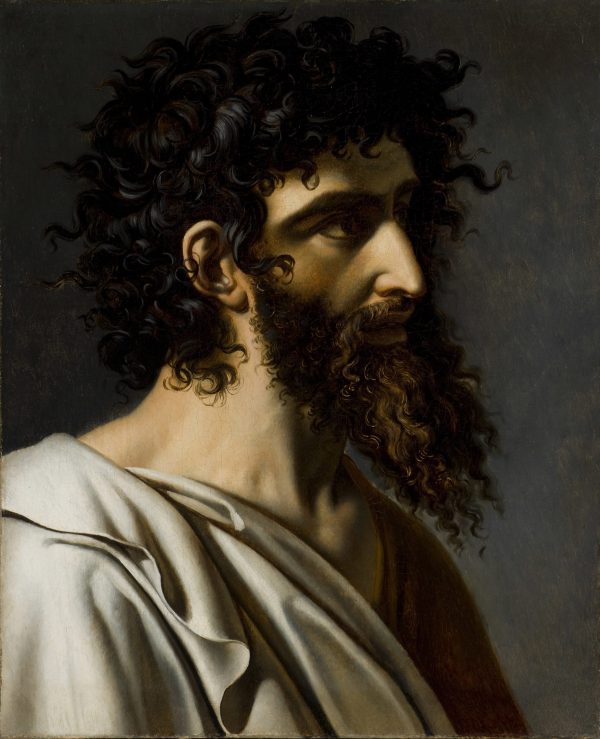

Portrait of Mordecai, Ca. 1790-1800

Oil on canvas, H. 0.61 m; W. 0.49 m

Provenance: The artist’s studio until his death.

Private collection, France.

- Sidonie Lemeux-Fraitot, « Inventaire après décès d’Anne-Louis Girodet-Trioson (1776-1824) », in Valérie Bajou et Sidonie Lemeux-Fraitot, Inventaires après décès de Gros et de Girodet. Documents inédits, Paris, 2002, rééd. 2003, p. 229, no. 196 : « sont attachés à la porte d’entrée les trois tableaux Suivans tête de Mardochée prisée trente francs (…) ».

- Jean-Marie Voignier, « La fortune de Girodet », Bulletin de la Société d’émulation de l’arrondissement de Montargis, no. 128-129, avril 2005 : Etat descriptif des objets d’art et autres effets mobiliers dépendant de la succession de M. Anne-Louis Girodet, p. 27, no. 196 : « sont attachés à la porte d’entrée les trois tableaux suivans : la tête de Mardochée prisée trente francs (…) »

Anne-Louis Girodet de Roucy, known as Girodet-Trioson, one of the major painters of the French School, is a primary figure in the transformation of French art between the Revolution and the Restoration. His oeuvre does not enter the categories of Neoclassicism or Romanticism. While pursuing the principles of the School of David, his teacher, Girodet also distorted the rules in combining representation with the unearthly and the mysterious.

Sent to Paris at an early age, where classical studies revealed his literary and artistic abilities, he had the Doctor Trioson as a tutor, whose adopted son he later became. In 1784, he began working in David’s studio and prepared for the Prix de Rome, which he won in 1789 with the Story of Joseph and his Brethren (Paris, Ecole nationale des Beaux-Arts), a work highly influenced by David. It was at this moment that he put significant distance between himself and his teacher, which he increasingly expressed in his painted works. His The Sleep of Endymion (Paris, Musée du Louvre), completed in September 1791, demonstrated this rupture: it is the subjective that influences reason. The painting enjoyed great success and founded his reputation as an original and poetic painter.

At the same time, Girodet had already begun to prepare the major painting of his stay in Rome: Hippocrates Refusing the Gifts of Artaxerxes (Paris, Faculté de Médecine), painted out of friendship for his guardian, Doctor Trioson, whose profession inspired the subject of the piece. Having begun immediately after completing Endymion, the painting exhibits an entirely different approach. Girodet adopts the style of David, as much through his artistic vocabulary as through his choice of subject, which in fact remained the only exemplum virtutis among Girodet’s works. The piece portrays a Greek doctor who refuses to treat the King of Persia, whose country is ravaged by the plague. The king’s ambassadors, dressed in white as a sign of mourning, are depicted in a Poussin-like manner, expressing a whole spectrum of emotions.

While it is not a preparatory study, Mordecai shares stylistic similarities with the aforementioned painting. Indeed, we find a reduced range of colours, with a white cloth, soberly draped, in Greco-Roman style, over an ochre tunic. The background is also neutral, and the tones of grey find an echo in the highlights of the subject’s hair and skin tones. Girodet is invested in representing a real feeling: the expression of the eyes and the parted mouth are touched with a softness and profound spirituality.

In January 1793, following the pillage of the Mancini Palace, home of the Académie de France in Rome, Girodet was able to escape to Naples with the remaining residents. On the road back to France, in Genoa, where he was held up by illness, he painted his Self Portrait (1795, Musée de Versailles) for Gros, who had come with the Italian army, which he traded for his friend’s own self-portrait. This painting has many points in common with Mordecai. The artist portrays a monochrome grey backdrop and the subject in a similar position, with one shoulder covered in a white cloth, the other in an ochre tunic.

Between 1798 and 1819, Girodet painted a dozen Oriental bust paintings of male subjects, half of which have been located today. These busts, featuring flamboyant colours and luxurious clothes, were painted in quite a different style from that of Mordecai. Among these we find Portrait de Mustapha, 1819 (Montargis, Musée Girodet).

During the final years of his life, Girodet decided to have several of his works lithographed by Jean-Joseph Dassy (1791-1865), a painter and lithographer from Marseilles who was one of his best students. He lithographed three bust studies: Mardochée (Mordecai), Mustapha, and the première étude pour Galathée, as well as Héro et Léandre (see Sidonie Lemeux-Fraitot, A l’épreuve du noir : Girodet & la lithographie, Montargis, 2010, p. 15-17). This choice revealed Girodet’s preference for these works and a desire to increase their visibility. He exhibited these prints at the Salon in 1824, where Mordecai and Mustapha were displayed together (Salon de 1824, no. 2095-2098).

The names Mordecai and Mustapha can be identified by Dassy’s prints, who placed a candle holder with seven branches placed under the name of Mardochée and a crescent under the name of Mustapha, recalling Jewish and Muslim symbols.

Traditionally, the biblical character of Mordecai is depicted as an old man dressed as a beggar. In our painting, however, Mordecai is a young man, seemingly like the Assyrians from his Hippocrates Refusing the Gifts of Artaxerxes. His voluminous hair, with unruly curls and messy beard, make him seem like an ancient prophet or even a Saint Jean-Baptiste figure. This man was in fact a real person named Mordecai, who posed as a model for various artists in Paris during the 1790s.

Our painting remained in Girodet’s studio until his death, and appears in his post-mortem inventory under number 196 (Tête de Mardochée, see Sidonie Lemeux-Fraitot 2002 et 2003, Voignier 2005). As Pérignon says for other bust studies, Mordecai probably served as a model for the students in Girodet’s studio (see Sidonie Lemeux-Fraitot 2003, p. 309 : « Pérignon no. 49 p. 16 : Etude d’après un vieillard endormi ; cette étude est très terminée jusque dans ses moindres détails. Ainsi que les deux précédentes elle servait de modèle dans l’atelier des élèves. ». After his death, our painting must have been conserved by the family, or otherwise given or sold to a family friend or a student, for it neither appears in the records of the artist’s studio sale (Jean-Marie Voignier, 2005, p. 57-92.), nor in the “List of the main works of Girodet” published in 1829 by Coupin (P. A. Coupin, Œuvres posthumes de Girodet-Trioson, peintre d’histoire : suivies de sa correspondance, Paris, 1829, t. I.) and based on the catalogue of the aforementioned sale.

After a second examination of the picture on November 5th, 2012, Mr Sylvain Bellenger is not convinced that our painting is by Girodet. After several examinations of the painting, Mrs Sidonie Lemeux-Fraitot confirmed her will to include Mordecai in the catalogue raisonné of Girodet that she is currently preparing.

As other art historians, we are convinced that this head study was painted in the 1790s, still under David’s influence, and not in the 1824s. On the back of Mordecai of the Becquerel collection, it is mentioned that it is a copy by Pérignon, and this picture does not support the comparison. Our conviction is that our painting is an authentic work by Girodet and was used as a model for the Becquerel version.

We are most grateful to Mrs Sidonie Lemeux-Fraitot for her help in writing this information sheet.