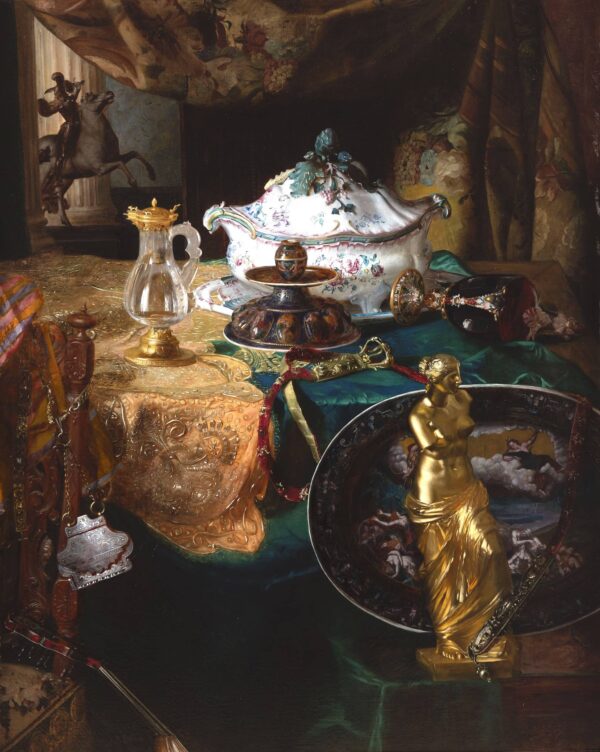

Still Life with Venus de Milo, 1860-1875

Oil on canvas, H. 1.00 m; W. 0.80 m

Signed lower right: Blaise Desgoffe

Provenance: Collection Samuel P. Avery etc sale, New York, Leavitt Art Galleries, 9-10 April 1878, no. 146, “Objects of Art from the Louvre and Hotel Cluny”, 39 x 31 [inches].

Private Collection

Fascinated by objects of art, Blaise Desgoffe became what might be called a “portraitist of collections”. His virtuoso and delicate art contributed to the cult of objects, reflecting during the second half of the 19th century, the fascination for inventories, and the interest in classification and dissemination of works of art held in public and private collections.

Blaise-Alexandre Desgoffe (1830-1901) was born in Paris, where he attended the prestigious Collège Sainte-Barbe. His innate penchant for drawing benefited from the benevolence of his uncle Alexandre Desgoffe (1805-1882), the famous painter of historical and decorative landscapes, an outstanding disciple of Ingres and distinguished member of the Institut. Blaise Desgoffe enrolled in the Paris École des Beaux-Arts in October 1852 and trained with his uncle’s son-in-law, Hippolyte Flandrin (1809-1864), another pupil of Ingres. This immersion in the world of Ingres fuelled the artist’s interest in the meticulous rendering of materials using an illusionist technique. He also studied under William Bouguereau (1825-1905), with whom he formed a lasting friendship. Desgoffe married Camille Bastid in 1857 in Clermont-Ferrand. They had four children, two of whom, Auguste and Jules,[1] would become artists.

Portraits of Objects of Art

Blaise Desgoffe specialised in depicting jewellery, weapons, and antique draperies, and made still life paintings of decorative art objects and curios. This new theme was almost exclusively associated with the 19th century,[2] although gold and silver objects with beautiful forms had been depicted on occasion in earlier centuries. Some painters began to make actual portraits of valuable objects, arousing interest in the evocative quality and historical value of the models. This fashion for depicting art objects in museums flourished in the second half of the 19th century. It should be seen in the context of the fascination for objects[3] that responded to the century’s passion for inventories, the taste for classification and the dissemination of works of art held in public and private collections.

The Salon livrets list around ten painters who exhibited this type of painting.[4] For Michel Faré,[5] Blaise Desgoffe was undoubtedly the driving force behind this and became very well known.

Desgoffe at the Salon

Blaise Desgoffe made his debut at the Salon in 1857 and exhibited there regularly until his death in 1901. In his first year, two of the four paintings he exhibited were still lifes, Oriental bowls from the Louvre’s Room of Jewellery. No doubt encouraged by the positive feedback, he continued this subject matter throughout his career, exhibiting 71 other still lifes of art objects at the Salon.[6] Desgoffe also exhibited at the Galerie George Petit in Paris during 1893. Like many contemporaries, after the Paris Salon he sent his paintings to provincial events, showing at seven salons in Bordeaux,[7] and also in Nantes,[8] Rouen, Lille,[9] Marseille, and Toulouse.

Desgoffe sold his first painting to the State at the 1859 Salon, a still life of an Amethyst Vase.[10] At the 1861 Salon, he won a 3rd class medal and the Empress Eugénie bought two of his compositions. Further official recognition came at the 1863 Salon: he was awarded a 2nd class medal and sold a second work to the State.[11] Thanks to a 1st class medal at the 1866 Salon, Desgoffe became “exempt from competition”, allowing him to exhibit there without submitting to the jury. After a long break of sixteen years, and in response to a request from the artist, the State bought a third painting from him in 1879.[12] Desgoffe was then awarded a bronze medal at the 1889 Universal Exhibition, and then sold his extraordinary painting, which was shown at the 1890 Salon, Circus Helmet (Musée des Beaux-Arts de Tours) to the State.[13] Between 1886 and 1901, the Société Française des Amis des Arts bought nine still lifes from him at the Salon.[14] He was made a Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur in 1878. Shortly before his death on 1 May 1901, Desgoffe was able to celebrate a fifth acquisition by the State of one of his works at the Salon, a painting of a display case from the Louvre’s Apollo Gallery (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Bordeaux).[15]

Desgoffe’s success waned over time, until he fell into obscurity from the 1890s. Shortly before his death, Desgoffe occupied a small flat in Paris, where he had been living alone since his wife returned to Clermont-Ferrand. When he died, he still owed three and a half years’ rent to his landlord and the estimated value of his furniture was 710 francs.[16] The posthumous inventory does not mention any paintings.

Assiduous Work at the Louvre

The objects of art represented by Desgoffe[17] were mainly made from gold and silver, painted enamels, majolica and weapons. However, it was gems, and rock crystals in particular, as seen in our painting, that most inspired him. The choice of objects shown also reflected the tastes of his time. Desgoffe was above all interested in objects from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, with a particular fondness for the extraordinary collection of Charles Sauvageot (1781-1860), which was donated to the Louvre in 1856.

Although other artists[18] also painted objects of art from the Louvre’s displays, none did so with the assiduity and constancy of Blaise Desgoffe, who worked in its spaces for forty-six years. Isabelle Balandre[19] cites the letters, now preserved in the Archives des Musées Nationaux, in which he requested permission to paint in specific rooms. Thanks to his fame, his familiarity with the museum, and his relations with the staff, objects were taken out of their display cases and in the evenings, Desgoffe would return them to be locked up again. He spotted certain small rooms in the museum, some of which were closed to the public, where the quality of the light, essential for his work, seemed ideal.

Fervent clients in Europe

From the second half of the 1860s, Desgoffe was sought after by wealthy bourgeois and aristocratic clients who owned large collections of objects from which the painter regularly created still life paintings. This was the case for Marble Statuette, Agate Vase, Persian and Indian Material, exhibited at the Salon of 1865, owned by the Ottoman banker Théodore Baltazzi.[20] Two compositions exhibited at the 1869 Salon show pieces from the collection of the Count of Nieuwerkerke, Director of the Imperial Museums. Desgoffe’s patrons also included the Comte Welles de la Valette,[21] the Duc de Morny, Prince Stirbey, Comte de Camondo, Madame Boucicaut, the Marquise de Tholozan, the Prefect of Police Symphorien Boittelle, the Vicomte de Saint-Albin, librarian to the Empress Eugénie, and Louis Marcotte de Quivières, Chassériau’s collector and patron.

Between 1879 and 1881, Desgoffe visited London several times, where he painted objects from Sir Richard Wallace’s collection at Hertford House.[22]

Praise in the United States

In the United States, the craze for European art was at its height in the second half of the 19th century, and Desgoffe became one of the most popular artists there. From the 1870s onwards, American journalists and art critics sang his praises and invited local artists to take inspiration from his creations.[23] The painters William Michael Harnett (1848-1892) and William Merritt Chase (1849-1916),[24] were influenced by his descriptive paintings of objects.

Our painting comes from the collection of Samuel Putnam Avery (1822-1904), a New York art dealer, wood engraver and collector of rare books and prints, who was one of the founders of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. By importing French and European art, he played a crucial role in building up American collections. During his visits to Paris, he cultivated his contacts with artists and commissioned works for clients such as William Henry Vanderbilt, the railway magnate, whose 1883 description of the collection includes a painting by Desgoffe.[25] For many years, Avery appears to have been an important client. In 1879, the year after he sold our painting at auction, he again commissioned a work from him.[26] His American customers also included John Wolfe (1871) and his cousin Catherine Lorillard Wolfe (1874), who ordered a painting from him showing a selection of her favourite objects from the Louvre.[27]

The Objects in our Painting

Our painting probably dates from the 1860s, when Blaise Desgoffe practised an extremely fine, polished manner. He illustrated his skill in reproducing precious materials and the play of light on their surfaces perfectly. Here, he has created a luxurious composition based on objects of art rivalling in luxury, most of which were from the Apollo Gallery in the Louvre. This variety of objects seems not to be connected in any way. Desgoffe, who would never have seen them all together, has ‘portrayed’ each one separately, seeking to attract attention in a dazzling composition. Although their proportions are not scrupulously respected, they are all real and recognisable, faithfully described down to the smallest detail. It is as if he were inviting his audience to play a guessing game, offering them the opportunity to comment on these magnificent pieces.

Tapestry from the Manufacture Royale des Gobelins

A tapestry hanging theatrically occupies the upper part of the composition. This is an “alentour” tapestry, here with a border imitating yellow damask, produced by the Manufacture Royale des Gobelins during the second half of the 18th century. It may be a part of a tapestry series with episodes from the story of Don Quixote.[28] This tapestry series, woven several times between 1717 and 1794, was the Gobelins’ greatest success. Alentour tapestries have a central scene that are treated as a framed painting placed against a background imitating damask, usually decorated with garlands of flowers, medallions, attributes, and even animals.

The Horse in the Background

In the left background of the composition, a horse rears against the light in front of a fluted column. This is clearly not a polished porcelain figurine, in fact Desgoffe, perhaps for the only time, has reproduced a painting, Raphael’s Saint George[29] which entered the royal collection in 1665 and Desgoffe could have seen in the Louvre. In this painting, rather than the magnificent horse or enchanting landscape, the reflections on Saint George’s breastplate inspired him.

A rich orange silk satin fabric carefully sewn onto a green satin backing covers the table. It is embellished with tulle or organza embroidered with ribbons, which is complemented by a striped Indian woollen fabric skilfully placed on the back of the chair.

Rock Crystal Ewer

The most prominent object on this table is a rock crystal ewer,[30] which Desgoffe admired in the Apollo Gallery. It was carved in Paris during the mid-14th century from a single piece of rock crystal, a material especially prized by Charles V (1338-1380). The technique, considered an Italian speciality, was mastered by Parisian crystal makers in the 13th century. The ewer has a twelve-sided ovoid body with a wide, straight neck and an elaborate handle. Its silver gilt mount has been restored several times and includes elements from the 17th to the 19th centuries. Its shape with straight sides reflects that of contemporary goldsmiths.

Artichoke Tureen

This large covered oval tureen with four feet sitting on a white glazed earthenware stand is decorated with polychrome flowers, some of which are in relief. The lid features an artichoke, foliage, and fruit in relief, while a purple combed pattern and green and yellow filets decorate the edges. It was made at the Manufacture de Sceaux around 1760[31].

Limoges Candlestick

A polychrome enamel candlestick with a dark blue background partly on foil, sits just in front of the tureen. It is one of a pair of candlesticks illustrating the Labours of Hercules[32] that Desgoffe noticed in the Apollo Gallery. Created in Limoges around 1600, this candlestick is inscribed “IC” in gold on the reverse, identifying it as the work of the “Master IC” who was formerly thought to be Jean Courteys or Jean de Court. This candlestick has a wide, convex, circular base with twelve projecting gadroons, and a flat disc topped by a baluster-shaped vase. The gadroons are set against a blue background strewn with fine gilded foliage, alternately representing six labours of Hercules and six gods. The body, or baluster shaped vase, reproduces the Triumph of Amphitrite after Jacques Androuet du Cerceau (1520-1586).

Sardonyx Ewer

Lying on the right side of the table, so it is not immediately recognisable, is a famous piece from the collection of King Louis XIV: a sardonyx ewer,[33] still on display today in one of the cabinets of the Apollo Gallery. It appears in several compositions by Desgoffe.[34] The brown sardonyx body of this large fluted vase, which dates to ancient Rome, was mounted by French silversmiths around 1665 and given an eagle-shaped spout, a handle representing a winged mermaid and a chased and enamelled gold base. From this unusual angle, Desgoffe shows us the mount’s base, decorated with white acanthus leaves where pink and blue highlights alternate with laurel leaves in translucent green enamel.

In Front on the Right: Niobids Platter, Venus de Milo and a Belt

In the right foreground, just behind the bronze statuette of the celebrated Venus de Milo,[35] Desgoffe has shown the famous Niobids Platter,[36] which was also on view in the Apollo Gallery. This is a polychrome enamel dish from about the 1580s with a black ground, partly on foil with gold highlights. Desgoffe has transformed it for the purposes of his composition; in reality, the dish is round, not oval. The scene depicting the massacre of the Niobids has also been altered to be visible on both sides of the Venus de Milo. Diana can be seen in the clouds and Apollo, standing right next to her on the plate, is shown by Desgoffe further to the left so as not to be hidden by the Venus de Milo. This platter is attributed to Martial Courteys, who was active around 1580, and is very similar to one painted by his father Pierre Courteys.[37]

At the Venus de Milo’s feet, Desgoffe has placed his signature in a cartouche attached to the end of a belt[38] from which a small ball hangs. This red velvet belt, whose gilded and chased copper buckle can be seen on the table, was created in Germany in the 16th century. Included in the Sauvageot donation of 1856, it was once displayed in one of the central showcases in the Apollo Gallery.

According to the title of our painting in the 1878 sale, some objects come from the Cluny Museum. The Neapolitan mandolin in the foreground, an instrument very similar to an 18th century example in the Musée de la Musique,[39] and the chased metal purse hanging from the chair, described in 1878 as a “steel tinder box and chain”, are confirmation of this.

[1] Jules Desgoffe (1864-1905) became a painter and exhibited at the Salon for the first time in 1886.

[2] Michel Faré, La nature morte en France. Son histoire et son évolution du XVIIe au XXe siècle, Geneva, 1962, vol. I, p. 250-251.

[3] Véronique Moreau, Peintures du XIXe siècle. Catalogue raisonné, vol. 1, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Tours, Château d’Azay-le-Ferron, 1999, p. 245.

[4] Painters of still lifes showing decorative arts objects include the following: Leprince-Ringuet, Georges Beniers, Louis Roedler, Antoine Vollon, Mme Claire Giard, Alphonse Hirsch, Jules Barbé, Julien Chappée, Félix Clouet (1806-1882), Charles Vallet, Jean-Pierre Lays (1825-1887), Mlle Louise Fery, Benoit Chirat (1795-1870) and his imitator Henri Roszczewski.

[5] Michel Faré, La nature morte en France. Son histoire et son évolution du XVIIe au XXe siècle, Geneva, 1962, vol. I, p. 250.

[6] Élisabeth Hardouin-Fugier, Les peintres de natures mortes en France au XIXe siècle, Paris, 1998, p. 295-296. And the Musée d’Orsay Salons database, https://salons.musee-orsay.fr/, consulted on 17 November 2023.

[7] Serge Fernandez, Pierre Sanchez, Salons et expositions Bordeaux. Répertoire des exposants et liste de leurs œuvres, 1771-1950, Dijon, L’Échelle de Jacob, 2017, vol. I, p. 519 (1859, 1869, 1896, 1898, 1900, 1901 and 1902).

[8] Pierre Sanchez, Salons et expositions Nantes. Répertoire des exposants et liste de leurs œuvres, 1825-1920, Dijon, L’Échelle de Jacob, 2016, vol. I, p. 307 (1894).

[9] Nicolas Buchaniec, Pierre Sanchez, Salons et expositions dans le département du Nord. Répertoire des exposants et liste de leurs œuvres, 1773-1914, Dijon, L’Échelle de Jacob, 2019, t. I (Rouen in 1891 and 1893; Lille in 1866).

[10] Still Life with an Amethyst Vase, oil on panel , H. 0,35 m; W. 0,27 m, long term loan from the Musée d’Orsay to the Musée des Beaux-Arts d’Arras.

[11] 16th century Rock Crystal Vase, Henri II’s wallet, enamels by Jean Limosin, etc, oil on panel, H. 1,25 m; W. 0,95 m, signed and dated at the bottom of the enamel niche, right: Blaise Desgoffe. 1862, Paris, Msusée d’Orsay, RF 81

[12] AN F/21/4304, Base Arcade, http://www2.culture.gouv.fr/documentation/arcade/ (consulted on 17 November 2023); and Isabelle Balandre, “Blaise Desgoffe, peintre passionné des objets d’art du Louvre”, Objets d’art. Mélanges en l’honneur de Daniel Alcouffe, Dijon, 2004, p. 405, note 29.

[13] Casque circassien, poire à poudre orientale du musée de l’artillerie, 1890, oil on canvas, H. 0,80 m; W. 0,60 m, Tours, Musée des Beaux-Arts (inv. 947-58-1).

[14] Isabelle Balandre, “Blaise Desgoffe, peintre passionné des objets d’art du Louvre”, Objets d’art. Mélanges en l’honneur de Daniel Alcouffe, Dijon, 2004, p. 405.

[15] Salon of 1901, no. 639: 16th century Reliquary, rock crystal, trinkets, etc [current title, The Apollo Gallery at the Louvre], oil on canvas, H. 1,00 m; W. 0,81 m, State purchase in 1901, exhibited at the Bordeaux Salon in 1902 (no. 176), in 1903 placed on long term loan at the Bordeaux Museum (Bx E 1181). See also Base Archim http://www2.culture.gouv.fr/public/mistral/caran_fr (Albums of State acquisitions from 1864 to 1901) consulted on 17 November 2023.

[16] The Paris notaire Maître Cottin’s archives have not been deposited. Cited by Isabelle Balandre, 2004, p. 405-406.

[17] Isabelle Balandre, op. cit., p. 400-407, p. 404.

[18] Henri-Dominique Roszczeski, Louise-Marie-Hortense Pauvert (1870-1950), ou encore Georges Croegaert (1848-1923), cf Isabelle Balandre, 2004, p. 406.

[19] Isabelle Balandre, op. cit., p. 402-404.

[20] When this painting was sold a year later (Sale Paris, Hôtel Drouot, Me Charles Oudart, 9 April 1866), it was specified that “this painting (…) was made for M. B…i, who provided the models of carpets and other objets d’art”.

[21] Saxony Porcelain, chalice, carpet from Smyrna, and Other Objects from the Collection of the Comte Welles de la Valette, oil on canvas, signed and dated lower right: “Blaise Desgoffe 1873”, H. 1,26 m; W. 1,05 m, 1874 Salon, location unknown.

[22] Still Life with Wallace Objects, 1880, oil on canvas, H. 1,00 m; W. 1,50 m, Sale Christie’s Monaco, 20 June 1992, lot 111, current location unknown. Olifant of St. Hubert, 1881, oil on panel, H. 0,25 m; W. 0,61 m, Chantilly, Musée Condé (inv. 542).

[23] William H. Gerdts and Russel Burke, American Still-Life Painting, New York, 1971, p. 135.

[24] Op.cit., p. 200.

[25] Edward Strahan, Mr. Vanderbilt’s house and collection, Boston, 1883-1884, volume 3, https://libmma.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16028coll4/id/33098/rec/1

(consulted on 17 November 2023)

[26] Letter from Blaise Desgoffe to Samuel Putnam Avery, 25 January 1879, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Samuel Putnam Avery papers”, https://libmma.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15324coll13/id/4132 (consulted on 17 November 2023) in which Desgoffe requests a payment of 1,500 or 2,000 francs for a painting that had been ordered (H. 0,73 m; W. 0,54 m).

[27] Objects of Art from the Louvre, 1874, oil on canvas, H. 0,73 m; L. 0,92 m, signed and dated lower left: Blaise Desgoffe / -74, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art (inv. 87.15.119).

[28] We are grateful to Arnaud Denis, inspector of the collections, in charge of the old tapestries, Mobilier national, for providing us with this information.

[29] Raphael, Saint George Fighting the Dragon, 1503-1505, oil on panel, H. 0,29 m; L. 0,26 m, Paris, Musée du Louvre (inv. 609).

[30] Rock crystal ewer, around 1350, 17th – 19th century mounts, rock crystal, modern gilt silver mounts, H. 0,25 m; W. 0,13 m, Paris, Musée du Louvre (inv. OA 62 A, MV 869), currently Richelieu wing, room 3).

[31] Large covered oval tureen on four feet and its presentation platter, about 1760, faience, petit feu decoration, H. 0,31 m; W. 0,39 m; platter: H. 0,36 m; L. 0,50 m, Sceaux, Musée de l’Ile de France (inv. 69.6.1). Exh. cat. Sceaux – Bourg la Reine. 150 ans de céramique, des collections privées aux collections publiques, musée de l’Ile-de-France, Sceaux, 1986, no. 57. Desgoffe could have painted this object at the National Ceramic Museum in Sèvres which has two examples (MNC 4174.1-2; MNC 26000/Cl. 7422).

[32] Master I.C., Candlestick from a pair: The Labours of Hercules, created in Limoges about 1600, Paris, musée du Louvre (MR 2504; N 1368). Currently on display in the Richelieu wing, room 20, display case 10. Sophie Baratte, Les émaux peints de Limoges, Paris, 2000, p. 358-359.

[33] Ewer, H. 0,24 m; L. 0,22 m, sardonyx 1st century B.C.- 1st century A.D., enamelled gold mount, Paris, about 1665, , Paris, musée du Louvre (MR 114). Les Gemmes de la Couronne, exh. cat. Paris, musée du Louvre, 2001, p. 49-51

[34] Objects of Art from the Louvre 1874, oil on canvas, H. 0,73 m; W. 0,92 m, signed and dated, lower left: Blaise Desgoffe / -74, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art inv. 87.15.119. Desgoffe painted the same ewer in three other paintings whose locations are currently unknown: Still Life, oil on canvas, H. 0,50 m; W. 0,36 m, Christie’s sale, New York, 16 October 1991, no. 3, Still Life, oil on canvas, H. 1,15 m; W. 1,51 m, Christie’s sale, New York, 30 October 1992, no. 1; Still Life with a Ewer, 1857, oil on panel, H. 0,46 m; W. 0,31 m, signed and dated lower left: Blaise Desgoffe 1857, Sotheby’s Paris, 10 November 2021, no. 140.

[35] A bronze reproduction of the famous Venus de Milo, the original Greek sculpture dating to the end of the 2nd century A.D. discovered in 1820 on the island of Melos, in the south-east of the Cyclades; Paros marble, H. 2,02 m, Paris, musée du Louvre (MA 399). During Desgoffe’s lifetime, different sized reproductions of this major object from the Louvre were already on sale.

[36] Martial Courteys (fl. 1544 – 1581, died in 1592), Round Platter: The Massacre of the Niobids, 1580-1590, painted enamel, diameter: 46,7 cm; hauteur: 5,5 cm, inscribed on the reverse “COURTOIS” Paris, musée du Louvre (MR 2412; N 1344). Now on display in the Richelieu wing, Room 20, display case 7. Sophie Baratte, Les émaux peints de Limoges, Paris, 2000, p. 364

[37] Rothschild Masterpieces Sale I, Christie’s New York, 11 October 2023, lot 14.

[38] Buckle and tab of a belt, Germany, 16th century, Paris, musée du Louvre (inv. OA 602).

[39] Neapolitan Mandolin, about 1790, Paris, Musée de la Musique (D.E.Cl.3484) on long term loan to the Renaissance Museum. We are grateful to Catherine Adam-Sigas for this information.