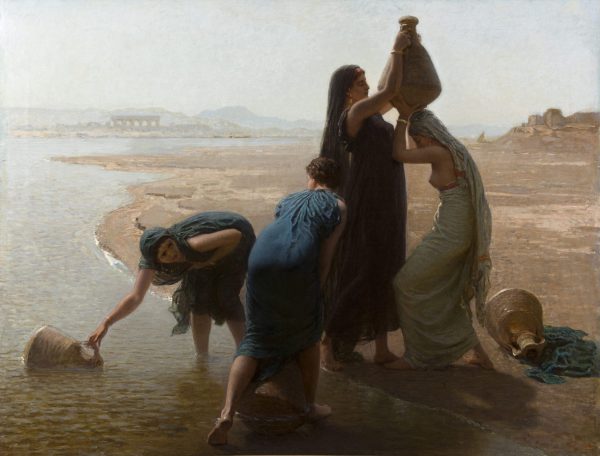

Fellaheen Women by the Nile, 1856

Oil on canvas, H. 0.98 m; W. 1.3 m

Bears the artist’s studio stamp lower right (red): L. BELLY and a printed label 3 on the lower left; chalk inscriptions on the stretcher: Bord du Nil Femmes fellahs and Rétrospective Belly 83.

Provenance: Sold to the Prince of Moskowa in 1863. Private collection, France

- Conrad de Mandach, “Léon Belly (1827-1877)”, Gazette des Beaux-Arts, février 1913, p. 143-157, our painting is discussed on p. 150.

- Patrick Wintrebert, Léon Belly (1827-1877), Premier essai de catalogue de l’œuvre peint, précédé d’une monographie. Mémoire de maîtrise, Université de Lille III, 1977, no. 94.

- Pierre Sanchez, La Société des Peintres Orientalistes français 1889-1943, Dijon, 2008, p. 95.

Having gained considerable renown with his masterpiece Pilgrims going to Mecca, 1861, which can be found today in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, Belly is above all considered an Orientalist painter. Born in Saint-Omer in the north of France, the artist was raised by his mother, widowed in 1828. A woman of means, cultivated, and a talented portrait miniaturist, she moved with her son to Metz, then Paris. Throughout secondary school, in which he thrived, Belly also developed a passion for painting, influenced by several of his mother’s artist friends. Following a brief stint in Picot’s studio, Belly established ties with the painters of the Barbizon school, most notably Constant Troyon. In 1850, Belly was a draughtsman on the scientific mission led by Caignart de Saulcy and Edouard Delessert to Palestine, aiming to study the historical geography of the region. There, Belly painted a handful of his most famous paintings, including Ruins of Baalbek (Saint-Omer, Musée de l’hôtel Sandelin). In October 1855, Belly departed on a second voyage to the Orient, and spent a year in Egypt. In April and May of 1856, he returned to the Sinai Peninsula with Narcisse Berchère. Between July and October 1856, he went up the Nile to Aswan in the company of painters Edouard Imer, Berchère, and Jean-Léon Gérôme, and the sculptor Bartoldi.

Fellaheen Women by the Nile is one of the major compositions that made a name for Belly at the Paris Salons. Belly produced this piece in Cairo in May and June of 1856. According to Patrick Wintrebert, this painting occupies a very particular place in Belly’s body of works: it was his first figure painting. Perhaps due to the influence of his friend Hippolyte Flandrin, Belly no longer wanted to confine himself to landscape, and aimed at mastering the genre of history painting.

A letter written to his mother, dated 1 June 1856, provides detailed information on Belly’s process in preparing Fellaheen Women by the Nile:

“This painting of women collecting water from the Nile is extremely interesting to work on, and is really teaching me to draw. It’s not enough to take the first graceful gesture that appears; you need to identify quintessential moments, and observe these simple and precise instants in depth, choosing the one that expresses the action in the simplest and most beautiful way – then study this same moment expressed by different women, with different lighting effects! The relationship between the people and the land is another study to do. I hope this painting will be good, for I know very well that I’m onto something, and I won’t let myself stop halfway. The painters who think they can be real by bringing back costumes and getting models to wear them, in paintings that depict scenes specific to a country, must be remarkably skilled to be able to pass as authentic…

Every evening, at about 4 o’clock, we go walking along the bank in Giseh to study the movements of the women who go to collect water; the air is fresh and delicious, and the landscape is, at that hour, marvelously beautiful. I can hardly set myself up there to paint, and I have to commit almost everything to memory. Once I am sure of the living movement, I use a model for the arms and the hands, but for the movement, once I have a model to pose I do not get it right any longer. A figure drawn and discovered in this way is worth 100 in the studio…I’m not working to create a painting, but to learn.”

A letter dated 22 June 1856 reveals that Belly was still focused on our painting. He began to set the positions of the women and studied their relationship to the surrounding land:

“I make sure the movement I need is performed one hundred times; I strive to capture it quickly in many hurriedly sketched drawings, drawings of isolated parts or of the ensemble. I now have to capture the effect of the figures in the countryside; beautiful things can be done in unifying these two elements.”

Indeed, in this skillfully constructed painting, the women’s movements keep their spontaneity and credibility. The elegance of the curves reveals Belly’s admiration for Ingres. As with Ingres, music played an important role in his life. An amateur pianist, Belly spent his Egyptian evenings playing music with Edouard Imer. A fervent admirer of Johann Sebastian Bach, Belly seems to have had a similarly precise and measured approach to painting.

Exhibited at the Salon of 1863, this work drew critics’ praise. Louis Emaut deemed it one of the best paintings of the Salon. He complimented the figures of the women, “admirably posed, with true demeanours, simple and poetic.” Arthur Stevens also called attention to our painting, adding, “I find this work to have stylistic intent that is very well received. Mr. Belly’s painting is easy.” Claude Vignon wrote, “Mr. Belly, the painter of Fellaheen Women by the Nile, brings us to a beautiful way of painting, to noble and firm drawing, to art of good taste.” A long commentary written by Théophile Gauthier similarly celebrated the piece: Mr. Belly’s Fellaheen Women by the Nile steps away from the usual, in which the landscape predominates, and it is a successful achievement in the domain of the human form.”