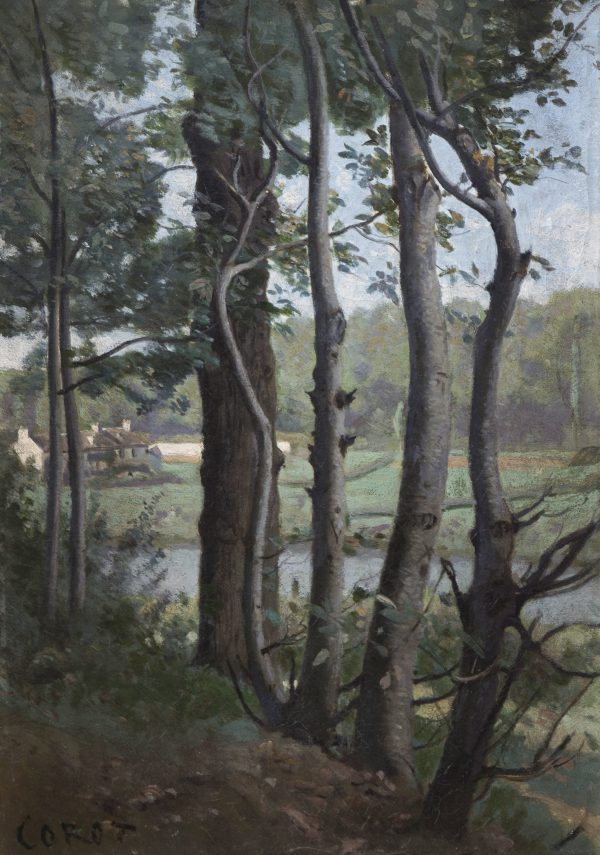

Les Evaux, near Château-Thierry, a Path bordered by Trees, 1855-1865

Oil on canvas, H. 0.4 m; W. 0.28 m

Signed lower left: Corot.

Provenance: Acquired at the beginning of the 20th century by Mr. Léon Labbé, who owned three works by Corot

Thence by descent

Private collection, France

With hindsight, we tend to think of Corot as the precursor of Impressionism.1 However, he is obviously a classical artist with a realist aspect, sometimes even showing some romantic tendencies. In his work, he combined the notion of classical beauty with truth and feeling.

Like Chardin before him, Corot emphasized the importance of sentiment in artistic creation. He thus advised his students: “Beauty in art is truth bathed in the impression we sense in the appearance of nature. I am moved when looking at an ordinary place. While seeking conscious imitation, I never lose the emotion that captivated me. The real is a part of art; the feeling completes it. With nature, look first for the form; after that, the relations or variations of shades, colour and execution; and all of this is to be submitted to the feeling you experienced.”2

After his first master, Achille-Etna Michallon (1796-1822) died, Corot spent three years in the studio of Jean-Victor Bertin (1767-1842). This painter passed on the conception of classical landscape he had received from Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes (1750-1819). In this way, Corot learned to work in situ to compose, and then in the studio to create landscapes to serve as the setting for a historical, biblical or mythological story.

The first paintings to be created en plein air go back to the 17th and 18th centuries.3 They were not just drawn, but also painted from nature. Italy occupies a prominent position in the tradition of plein air painting where it took off during the last two decades of the 18th century.4

The studies Corot painted during his first stay in Italy between 1825 and 1828 are striking in their vivacity and modernity. He kept them in his studio all his life and they were among the main attractions of his posthumous sale in 1875. They were only truly discovered by the public in 1906 when masterpieces by Corot were donated to the Louvre by Étienne Moreau-Nélaton. They could not therefore have influenced the Impressionist painters.5

It is important to remember that Corot’s fame was not based on these sketches, which were not intended to be shown in public, but on his developed compositions. Corot never exhibited his studies from nature at the Salon, but from 1835, more and more often he agreed to sell them. Gradually, in the artist’s mind, they became independent works of art.6

Throughout his career, Corot practised plein air painting when he was travelling around France and in Italy, the Netherlands and Switzerland. After 1830, Corot preferred canvas to paper as the support for his plein air work.

Corot was especially sensitive to landscapes in what today constitutes Picardy, the region where he had several friends. He visited there multiple times from the second half of the 1850s until 1872, three years before he died. Corot appreciated the fragile light there, the light mist of the humid countryside, and he developed his silvery palette there. Among the paintings created in the region is the famous Souvenir de Mortefontaine, 1864 (Paris, Musée du Louvre) a highly poetic and sentimental landscape painted in the studio from his plein air studies.

Château-Thierry is a picturesque town on the banks of the Marne between Paris and Reims. According to Etienne Moreau-Nélaton,((Etienne Moreau-Nélaton, Corot raconté par lui-même, Paris, 1924, t. I, p. 108.)) Corot visited the south of the Aisne département for the first time in June 1856. He stayed at Essômes, a town near Château-Thierry, with his friend Monsieur Hébert, who had formerly sold shawls in the Rue du Bac in Paris and who had retired there.7 Everything indicates that he was a friend of the family as Corot’s mother’s fashion shop was also on the rue du Bac, opposite the Pont Royal. Moreau-Nélaton describes this Mr. Hébert as a “man of taste who bought several paintings from him”.

In September 1856, Corot visited his friend and favourite pupil, Eugène Lavieille (1820-1889), who lived at La Ferté-Milon between 1855 and 1860, a town about thirty kilometres away from Château-Thierry.8 With Lavieille, he painted Château-Thierry and sites around it many times.

Corot returned to Château-Thierry at the latest for the wedding of one of his nephews, Jules Chamouillet, on 18 April 1863. Corot, who never married and had no children, was very close to his nephews all his life. This nephew married a daughter of an old family from the town, Marie-Henriette Boujot-Vol. The morning of the wedding, Corot set up his easel on the ramparts of the castle of the Counts of Champagne.9 He went there every morning and painted his famous View of the Ramparts of Château-Thierry (Lisbon, Calouste Gulbenkian Museum).

The catalogue raisonné lists six general views of Château-Thierry10 and three landscapes painted in the area11, close to our composition. The point of view chosen for our painting was probably taken from Les Évaux, near Château-Thierry, on the left bank of the Marne12.

The modernity of our painting is first in its subject matter. It shows a landscape without any mythological figures, who are not discussing anything and are claiming only truth. When it was created, historical landscape had fallen out of fashion as a genre; the Prix de Rome in this category was in addition abolished in 1863. Furthermore, the composition of our painting is resolutely modern. Corot shows us a landscape through a curtain of trees of which we only see the trunks. This close-up of the trees against the light, in front of a luminous landscape is formed by light vibrant touches of the brush. The silvery palette is entirely typical of the artist’s paintings created after 1850.

We are grateful to Mr. Martin Dieterle and Ms. Claire Lebeau for confirming the authenticity of this work. It will be included in the sixth supplement to the L’œuvre de Corot by Alfred Robaut that is currently being prepared.

- Zola considered Corot to be the first painter to break away from classical landscape as inherited from Poussin and the pioneer of plein air painting and of the “true feeling […] of nature” (Emile Zola, Mon Salon. Les paysagistes, 1868). [↩]

- Alfred Robaut, Etienne Moreau-Nélaton, L’œuvre de Corot: catalogue raisonné et illustré, Paris, 1905, t. I, p. 72. [↩]

- Philip Conisbee, “La peinture de plein air avant Corot”, Corot, un artiste de son temps, Conference papers, Académie de France à Rome (1996), Paris,1998, p. 353-373, p. 354. [↩]

- In the work of artists such as Simon Denis, Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes, Alexandre-Hyacinthe Dunouy, Jacques Sablet and Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld. [↩]

- Vincent Pomarède, “Le souvenir recomposé. Réflexions autour du thème du « souvenir » dans l’œuvre de Corot”, Corot, un artiste de son temps, Conference papers, Académie de France à Rome (1996), Paris,1998, p. 429 and note 9. The Impressionist painters admired what they knew of Corot’s work. Claude Monet, reviewing the 1859 Salon in a letter to Eugène Boudin, wrote enthusiastically that: “Les Corot sont de simples merveilles. [The Corots are simple wonders]” Gustave Cahen, Eugène Boudin, sa vie et son œuvre, Paris, 1900, p. 26. [↩]

- Vincent Pomarède, “Le souvenir recomposé. Réflexions autour du thème du « souvenir » dans l’œuvre de Corot”, Corot, un artiste de son temps, Conference papers, Académie de France à Rome (1996), Paris,1998, p. 429-430. [↩]

- Annales de la Société historique et archéologique de Château-Thierry, 1886, p. 127; Fédération des sociétés d’histoire et d’archéologie de l’Aisne. Mémoires, vol. VIII (1961-1962), 1962, p. 45; Frédéric Henriet, Charles Philippe de Chennevières-Pointel,Les Campagnes d’un paysagiste: Aisne – Seine-et-Marne. Précédées d’une Lettre sur le paysage par le Mis de Chennevières, Paris, 1891, p. 144: « (…) chez M. Hébert, ancien fabricant de châles, gendre de M. Pougin ». [↩]

- Annales de la Société historique et archéologique de Château-Thierry, 1934, p. 38. [↩]

- Alfred Robaut, Etienne Moreau-Nélaton, L’œuvre de Corot, catalogue raisonné et illustré, Paris, t. I, reprint 1965, p. 218. [↩]

- Alfred Robaut, Etienne Moreau-Nélaton, L’œuvre de Corot, catalogue raisonné et illustré, Paris, 1905, réimpr. 1965, t. II, no. 1016 à 1020. [↩]

- Alfred Robaut, Etienne Moreau-Nélaton, L’œuvre de Corot : catalogue raisonné et illustré, Paris, 1905, t. III, no. 1290 à 1292. [↩]

- Nous remercions Monsieur Stéphane Loire pour son aide dans la localisation de ce paysage. [↩]