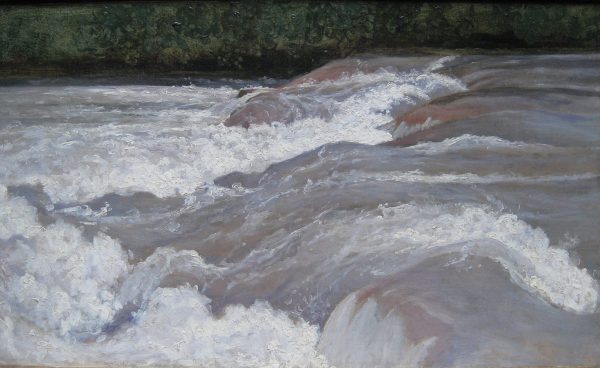

The Velino above the Cascade of Terni, 1826

Oil on paper laid down on canvas., H. 0.24 m; W. 0.39 m

Provenance: Henri Rouart (1833-1912), his sale Paris 1912, no. 133.

Captain Edward Molyneux.

Galerie Charpentier, 1945.

Georges Renand, acquired from the above, by descent.

Private Collection, Canada.

Alfred Robaut, L’oeuvre de Corot, Paris, 1905, vol. II, p. 46, no. 128 (ill.).

Germain Bazin, Corot, Paris, 1951, pl. 12.

Germain Bazin, Corot, Paris, 1973, p. 277 (ill. p. 136).

Peter Galassi, Corot in Italy. Open-Air Painting and the Classical-Landscape Tradition, New Haven and London, 1991, p. 103, ill. no. 118.

This open-air study of a rushing stream dates from Corot’s first stay in Italy. Corot had left France in the fall of 1825, together with Johann Carl Behr, another student of Bertin. They arrived in Rome in December of 1825. In the spring of 1826, they left the city to practice outdoor painting in the countryside. They spent August and September in Papigni and Narni (Robaut, 1905, vol. I, p. 36-37), about a hundred kilometres north of Rome. This site was known for its huge waterfall constructed in the Roman period, called the Marmore Falls (Cascade of Terni). The Romans had canalized the stagnant waters of the Velino to fall into the Nera river. According to Robaut , Corot has painted this study sitting besides the Lake of Papigno which the Velino river flows into just before the falls. (Robaut, 1905, vol. II, p. 46, no. 128 : Robaut dates the picture of 1826 and his title is “Le Velino à la sortie du Lac de Papigno”.)

As part of his classical training as a landscape painter, Corot spent most of his time in Italy drawing and painting outdoors. Robaut recorded more than 150 small landscape paintings from this period. These small studies were not meant to be shown to public. As advocated by the theoretician Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes (1750-1819), their primary purpose was to establish the principal tones of the sky, earth, and water through the lighting of the landscape at a particular moment. They generally did not serve as compositional models for particular paintings. Rather, they would be idealized by classically trained painters in landscapes produced entirely in the studio.

Upon returning to France, Corot followed the established practice of displaying his landscape studies in his studio, as sources of inspiration and instruction. This remained a life-long habit and Corot apparently valued his early studies very highly. Robaut recorded an episode of the early 1870s in which Corot admonished a young painter for spending so much time copying Corot’s latest studies, saying “Because, in the end, one learns nothing from those, whereas with my old studies it’s something else again.” (Alfred Robaut, Documents sur Corot, vol. II, p. 85.)

According to Robaut, Corot has kept the present study in his studio until a few months before his death. Its subject is quite outstanding in Corot’s oeuvre, who was rather a painter of silent waters. This powerful study shows the inherent qualities of a sketch, namely the lively effect produced by its energetic brushwork, vibrant colours, and bold contrasts. Its format of the closely cropped detail of the river reveals an impressive freedom of organization. It is a somewhat abstract study of rushing waters, a vibrant and truthful rendition of nature. With good reason, Corot was regarded as a precursor to the Impressionists for his outdoor painting.